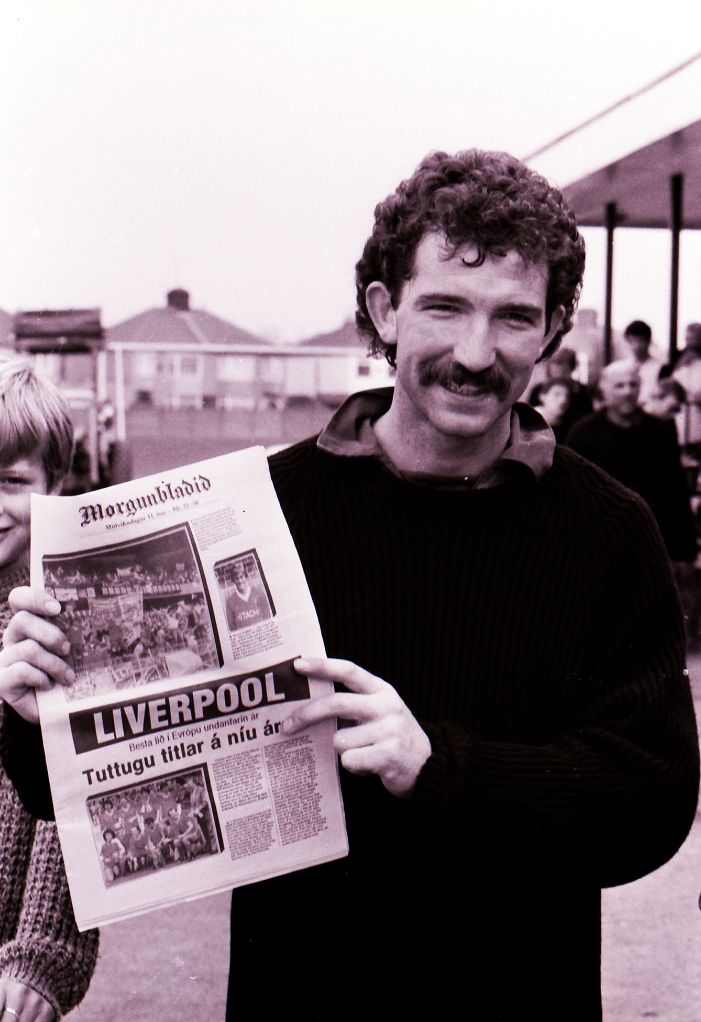

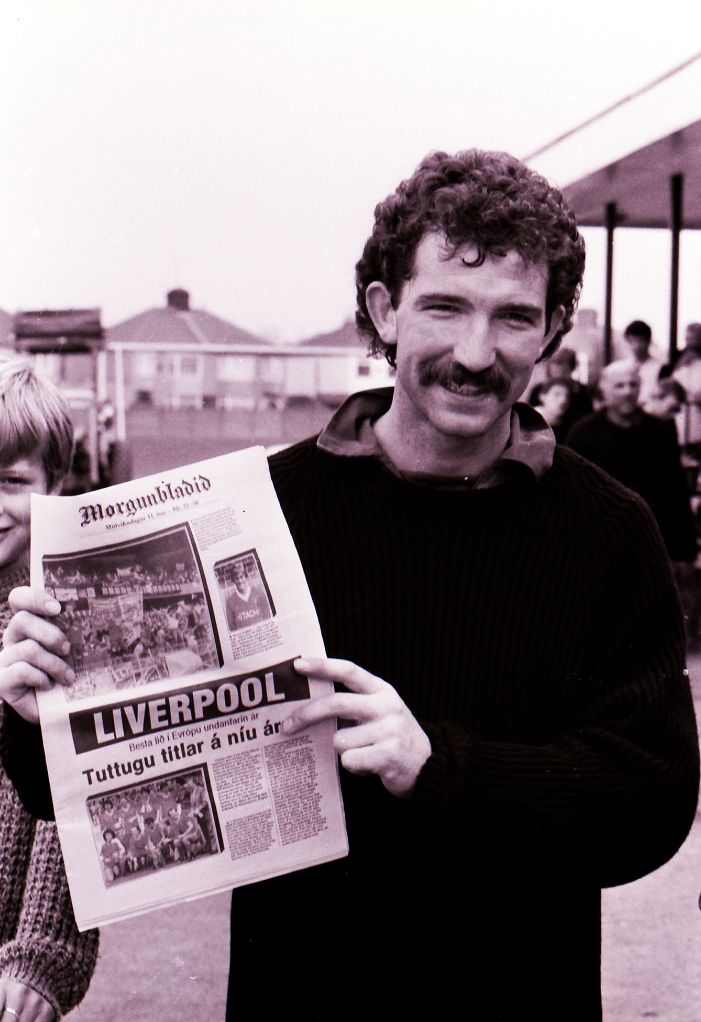

Graeme Souness at Melwood in 1984. Image copyright - Skapti Hallgrímsson

All historians should be nicknamed ’Hindsight’. We are expected to uncover the reasons for rise and fall, for triumph and failure, for trends and sudden incidents. In so doing, however, we might also insert drops of reality into the myths and legends, heroes and villains, of the subject under investigation. When Liverpool won the premiership title in 2020, the media was full of ‘first time since …’ and ‘… after a long, thirty-year wait’, but not ‘the gap caused by’ or ‘giant had slept because…’ It was left to historians to pick over the bones of our failure to live up to expectations, during a period made worse by the temporary successes of that lot down East Lancs Road.

There are two obvious targets on whom to pin the blame for Liverpool’s sudden fall from the heights to which we believed we had become entitled, as well as accustomed. Ironically, both loved, and were loved by, the club; both apologised for their unintended part in its decline. Equally ironic, one was too fast for the club’s own good, whereas the other was too slow. The fall was so sudden that, at first glance, you could even time it to September 1991. Going into the game against Leeds on the 21st, we had been third in the First Division table; at the end of the game, we were ninth, albeit with a game in hand, falling to 13th a week later. We’d not been that low since 1984. Ignoring the first three games of the season which are always statistical aberrations for this purpose, our average league position had been 2.5; after this game it was 6.4. A season later, our average league position was 12.6. In 1990/91, it had been 1.2, so the decimal point had moved to the right in only two years!

The seasons before the decline are too well known to need repeating in any detail – the Heysel and Hillsborough disasters took their toll on the whole club and its fanbase. The most recent manager, Kenny Dalglish, struggled with the latter event and its aftermath until he felt it necessary to resign. Ronnie Moran took over for 52 days until, on 16 April 1991, a successor had been appointed on the tried and trusted Liverpool basis. Graeme Souness had been (like all managers since Shankly) a popular player for LFC but also brought the experience of having been a successful player manager for five years at Glasgow Rangers. Perhaps this was the board’s deciding factor over the favourite for the job, Alan Hansen. It might also have been his recent experience of playing in European competitions, from which England had been banned since Heysel in 1985.

Another front-runner would have been John Toshack, who had returned to managing the club where he’d already had considerable success, Real Sociedad, only a couple of months earlier.

Hansen was not the only leading light in the Liverpool squad to aver later that Graeme Souness ‘was the perfect choice to succeed Kenny Dalglish’. Ian Rush writes in his autobiography, “If anyone had the qualities to keep Liverpool at the top, it was him.’ Liverpool lost only one of the first seven matches in 1991/92, that against MCFC by the odd goal. They took Everton apart, despite facing their neighbour’s newly acquired Peter Beardsley, and without Steve Staunton, who had also been sold. Barnes, Rush and Wright were injured. ‘Clearly the Kop can look forward to further treats,’ concluded the Guardian.

The game on 21 September 1991 was at Elland Road against a high-flying Leeds United whose forward line included Gordon Strachan, Lee Chapman, Gary Speed, and (later our own) Gary McAllister. (We’d done the double on newly promoted Leeds, who had those four up front, during the previous season. In fact, Leeds hadn’t beaten Liverpool since 1973.) Our own forward line were no slouches – Dean Saunders, Ray Houghton, Ian Rush, Mark Walters, and Steve McManaman, and we’d just come off a 6-1 win in the first round of the UEFA Cup.

So what went wrong on the pitch? The absence of Barnes, McMahon and Whelan does not explain why this loss was not just a one-off. There were other injuries too – Hysen, Molby and Venison were unavailable. ‘Is it any wonder that Liverpool are struggling?’ asked The Times. Reporters also noticed a slowness to Liverpool’s game that day, a lethargy, offering only mundane play. One likened Rush to a ‘cockerel in a farmyard where a fox had killed all the chickens’. Even worse was the judgement that Leeds had not played particularly well, yet LFC had been (in Phil McNulty’s words), ’second in just about everything.’

The pundits of the day did not foresee what was to come, but judged 21 September 1991 as a one-off poor result, largely brought about by Liverpool’s injury list and Rush’s below-par fitness. The only criticism of new manager Souness was being lectured by a ‘finger-wagging’ referee after he and Ronnie Moran had been raging about Leeds’s time wasting. The Liverpool manager did not attend press conference after the match and left early after the next game (Sheffield Wednesday 1-1), evidently in a foul mood following our poor second half showing.

By the time we lost to Crystal Palace, whom we had walloped 9-0 a few months earlier) on 2 November, it was clear that Liverpool had already shot its bolt. There was to be no challenging for the title, let alone keeping it. We played fifteen more games later that season without scoring a goal. Despite a revival after Christmas and winning the FA Cup, we were in sixth place from the time of Souness’s heart operation in April to the end of the season, but the blame was by now falling squarely on the manager whose experience of playing in Italy had convinced him of the need for a much stricter training regime. It was the background to Hansen reportedly playing a trick on his colleagues by announcing that, instead of retiring, he had been appointed manager and told the team that he would be instituting a new, harsh training and dietary programme including a ban on alcohol.

A ’fitness freak’ Souness (as he still is, of course) was soon to be blamed for the rash of injuries which hindered his first full season as manager. Rush talks of the new regime echoing Hansen’s joke - far more running included in training, for example, new, healthy diet and lifestyles which were unpopular with players, but also organisational changes within the club, seemingly for their own sake. This was five years before Wenger famously introduced similar changes at Arsenal, being widely credited with the innovations.

Souness’s hospitalization on 6 April 1992 was (and still is by many) widely believed to be an accident waiting to happen, his emphasis on physical fitness, combined with the considerable stress of managing a famous club in decline, providing a classic, deadly combination. Four days earlier, he’d been told of the danger he was in by the club’s doctor but told few people (coach Phil Boesma was one) until he confided in the team on the way back from the first FA Cup semi-final on 5 May. Needless to say, that revived a media investigation into his private life, photos of estranged wife and girlfriend with their apparent likeness, and dislikeness, being shown to the world, and (probably even worse for Souness himself) his children’s reaction. Just what you’d want as a background to a triple by-pass operation! Luckily, the private hospital did not have a satellite dish, so he avoided going through the stress of watching the semi-final replay!

Ironically, all that stress added together would not have caused his medical condition. As early as 6 April, the Sandwell Evening Mail could report that the fault lay in Souness’s genes, an inability to control cholesterol which had caused his father to need the same procedure. The manager’s operation was delayed by, not caused by, his emphasis on physical fitness. That revelation, however, doesn’t sell newspapers – nor does an apparently missing investigation into why the club’s medics were not aware of the problem earlier. Souness did not have a medical as a condition of his appointment, so carried his ticker-ticking timebomb into the dugout. Nor, despite the level of salaries and activity involved, has any LFC manager since.

David Lacey’s report of the FA Cup semi-final replay against Portsmouth on 13th April 1992, with Souness still in his hospital bed, describes a scare in the 85th minute as ‘a bad moment for more than one Liverpool heart’. The manager then had to sit, or lie, through a penalty shoot-out.

It was also the occasion when the very newspaper whose circulation had plummeted in Liverpool, and beyond, since Hillsborough, chose to exploit Souness’s ill-judged willingness to be interviewed in hospital. The paper whose name shall not be mentioned, had already run one article on the subject (according to the Edinburgh Evening News) which said Souness hoped to be back at Anfield by 9 July. I’m astonished that any hospital would allow such press intrusion in Souness’s condition, but his lifestyle had already given him celebrity treatment. The article could perhaps be seen as an attempt to curry favour with the fans who were understandably anxious to get news of the manager; but the editorial decision to publish by that paper on 15 April, the anniversary of Hillsborough, made it look suspiciously like vengeance for lost sales, and the manager got the full force of the fans’ backlash.

However, despicable the paper, the publication itself was not a cause of Liverpool’s decline, which continued until the end of the 1993/94 season. We finished the 1992/93 season in sixth place once again, but had been in double figures for almost the whole year - not even good enough to get into the UEFA cup, then. Even from these few overall figures, there is a strong connection between Souness’s time as manager and the results. Relatively poor recruitment made LFC’s position worse - but surely he was not responsible for a thirty-year decline? Anyway, what decline? Even before Klopp’s arrival, our record in the years of ‘decline’ involved five FA cup finals (winning three of them), five League Cup finals (winning four), finalists in the Champions League (winning one on that glorious day in Liverpool’s history), and winning a UEFA Cup. Houllier, Benitez and Rodgers all achieved a Premier League runners-up position.

But none won the League title, without which fans mentally suffer a barren year.

Twelve of the squad which Dalglish bequeathed to Souness survived long enough to be managed by Roy Evans, who took over on 31 January 1994 after Souness’s resignation. Among those who had left by then (before transfer windows were introduced) were Gary Ablett, Glen Hysen, Barry Venison, Steve McMahon, and Ray Houghton. Souness’s two sixth-place finishes worsened to eighth under Evans, who then steadied the ship to two third and two fourth place finishes before even that was unsatisfactory enough to be the occasion for Gerard Houllier to be introduced alongside him. The disappointing recruitment of new players, and the slow promotion academy graduates during the early 1990s took over a decade to overcome, though the overseas connections of Houllier and Benitez dramatically changed the nationality complexity of their squads.

*

By a suspiciously strong coincidence, the second ‘obvious target’ for LFC’s thirty-year fall from grace also began in September 1991. David Moores, an exile from the football pools family which owned and successfully controlled Everton FC, had been a lifelong LFC supporter, became its chairman on September 18, 1991. The change was underwhelming enough to escape any immediate reference in the local press. We were used to the presence of Liverpool’s financial royalty in the boardrooms – indeed, I guess many fans would have been surprised to discover that anyone actually owned football clubs. Moores was certainly well liked, Robbie Fowler being almost effusive in his praise.

Yet it was the comforting ‘more of the same’, the loyalty to the club’s traditions and personnel, which contributed to Liverpool’s decline for, at the same time, competitors were developing as football itself was changing. Still reeling from the awful disaster of Hillsborough, the club was being swept along by the creation of the Premier League, the invasion of ideas from the continent, notably by Arsenal’s acquisition of Wenger, and the employment of a new breed of boffin, the football analyst which helped to kick-start the fortunes of Ferguson at Old Trafford by the secondment of Les Kershaw, a local chemistry lecturer. (He later became their chief scout.) The Association of Football Statisticians was founded in 1979.

Good, swift decisions in this new era were vital in order to bring the required rewards, not the awful managerial decision to have two managers simultaneously. Commercialization, however distasteful to many, needed to be embraced, while Liverpool dragged its feet, typified by the closure of the club’s shop after the inspiring miracle of Istanbul on the pitch. By the time David Moores had realised that his own commercial nous was not good enough for this new age, a new stadium was the talk of the town, and Moores decided to put his 51% share onto the market. Following the lead of the Glazers, who took over MUFC in 2005, Hicks and Gillett persuaded David Moores and the LFC board of their probity and good intentions, and became our owners in 2007. They appointed Roy Hodgson as manager to replace Benitez, one bad fit followed by a worse, until we were rescued by Dalglish and the present owners for the long haul back to where we were, fighting for trophies.

Copyright - Dr. Colin Rogers for LFChistory.net